non-governmental agencies, and our Canadian counterparts, to assist them in restoring the Great Lakes.

Embedded in the Great Lakes Restoration Initiative is the Action Plan, which describes the most significant ecosystem problems and efforts to address them in five major focus areas. There are multiple pre-existing plans implemented by federal, state, tribal, local and non- governmental stakeholders, which were taken into account when forming the Action Plan. The five areas of focus for the GLRI are (1) cleaning up toxic substances and areas of concern, (2) combating invasive species, (3) promoting nearshore health by protecting watersheds from polluted run-off, (4) restoring wetlands and (5) accountability, education, monitoring, evaluation, communication and partnerships. Let us look at each of the five focus areas in more detail...

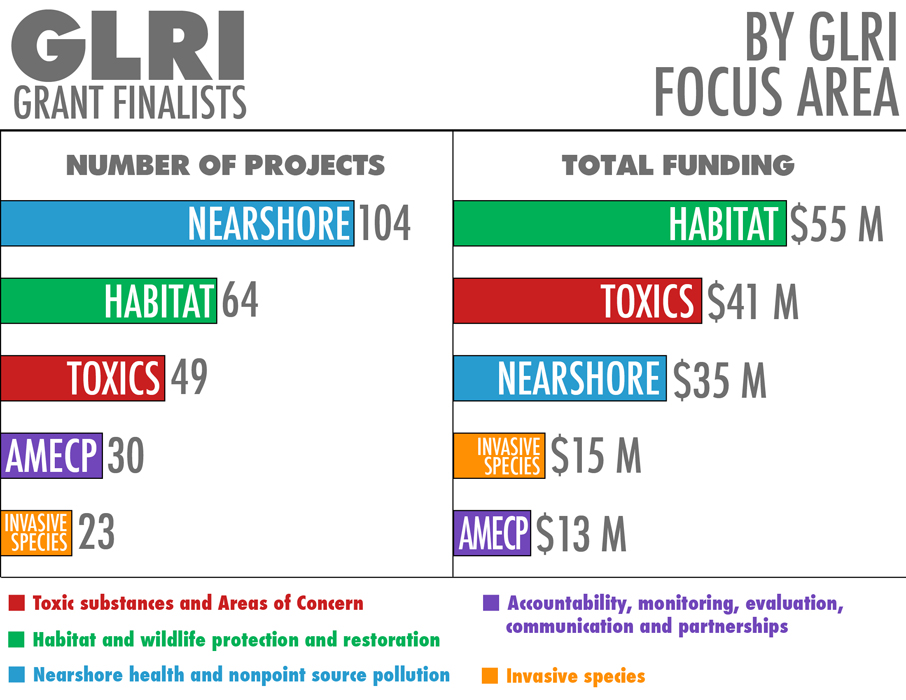

Breakdown of how Great Lakes Restoration Initiative Funding is spent.

- Cleaning up toxic substances and areas of concern: Toxic substances have become a huge problem within the Great Lakes. One group of substances that is found in the Great Lakes are heavy metals, such as mercury and lead. These chemicals are used within factories and get released into the air and water ways. PCB's, otherwise known as Polychlorinated biphenyl, "were used in a large amount of industrial and commercial applications which included electrical, heat transfer, and hydraulic equipment. They were also used as plasticizers in paints, plastics, and rubber products; in pigments, dyes, and carbonless copy paper as well as many other industrial applications" up until they were banned in 1979. Although banned for over 30 years, PCB's are a legacy pollutant. This means they remain present in the environment for long periods of time. PCB's, as well as numerous other legacy pollutants, are still found in the Great Lakes today. Pesticides are also found within the Great Lakes. This is largely due to runoff from the agriculture industry. When rainfall comes, the pesticides that were spread through out agricultural land are washed into the near by water ways. Agricultural facilities are considered non-point sources, which means their waste water can be dumped into waterways without facing regulation.

Map of Great Lakes signifying Areas of Concern, Areas in Recovery, and Delisted Areas of Concern.

So, how is the Great Lakes Restoration Initiative working to get these toxic substances out of the Great Lakes? One example is the Early Warning Program (implemented by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service) which was implemented to detect and identify newly emerging contaminants and their effects on wildlife in the Great Lakes. Some of these newly emerging contaminants include pharmaceuticals, personal care products, flame retardants, and current-use pesticides. Legacy pollutants are already a problem in these waters, so identifying new contaminants as soon as possible is crucial. GLRI funds also go to projects that take the necessary steps to clean up contaminated sediment in areas of concern. The over all goal of the GLRI, when it comes to toxic substances, is to remediate contaminated sediments and to address other major pollution sources in order to restore and delist the most polluted sites in the Great Lakes basin.

2. Invasive species: Invasive species are a threat to all of the Great Lakes, and have been present there since Europeans settled in the region. As human activity increases in the Great Lakes area, so do the number of invasive species. The Great Lakes Information Network tells us, "Since the 1800s, more than 140 exotic aquatic organisms of all types - including plants, fish, algae and mollusks - have become established in the Great Lakes." Some of the invasive species you will find in the Great Lakes include...

So, how is the Great Lakes Restoration Initiative working to get these toxic substances out of the Great Lakes? One example is the Early Warning Program (implemented by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service) which was implemented to detect and identify newly emerging contaminants and their effects on wildlife in the Great Lakes. Some of these newly emerging contaminants include pharmaceuticals, personal care products, flame retardants, and current-use pesticides. Legacy pollutants are already a problem in these waters, so identifying new contaminants as soon as possible is crucial. GLRI funds also go to projects that take the necessary steps to clean up contaminated sediment in areas of concern. The over all goal of the GLRI, when it comes to toxic substances, is to remediate contaminated sediments and to address other major pollution sources in order to restore and delist the most polluted sites in the Great Lakes basin.

2. Invasive species: Invasive species are a threat to all of the Great Lakes, and have been present there since Europeans settled in the region. As human activity increases in the Great Lakes area, so do the number of invasive species. The Great Lakes Information Network tells us, "Since the 1800s, more than 140 exotic aquatic organisms of all types - including plants, fish, algae and mollusks - have become established in the Great Lakes." Some of the invasive species you will find in the Great Lakes include...

Zebra Mussels

Cluster of Zebra Mussels in the one of the Great Lakes.

Zebra mussels are a small, fingernail-sized mussels native to the Caspian Sea region of Asia. They are related to quagga mussels, which are also a problem within the Great Lakes. Zebra mussels were discovered in Lake St. Clair near Detroit in 1988. Given their tolerance for a wide range of environmental conditions, zebra mussels have now spread to parts of all the Great Lakes. Zebra mussels form large clusters which clog the water-intake systems of power plants and water treatment facilities, as well as irrigation systems, and the cooling systems of boat engines. Native mussel species are not capable of competing with zebra mussles and have therefore been significantly reduced or, in some areas, completely eliminated. There are numerous methods used when combating zebra mussels, although, never getting them in the first place is your best bet. Preventative methods are most highly recommended when it comes to zebra mussels. However, if they are already present, pre-chlorination, electric shock, high pressure water spraying, preheating, and sonic vibrations. The most common treatment is pre-cholrination, given that it is already approved by the Environmental Protection Agency. (http://www.nesc.wvu.edu/ndwc/pdf/ot/ots00.pdf page 16)

Phragmites

Native and non-native phragmites in the Great Lakes.

Phragmites, also known as common weed, is a wetland plant species that is found through out the United States, Europe, Asia, Africa, and Australia. Since it is found in so many places, how this non-native strain of phragmites got to the Great Lakes is hard to figure out. There is widespread belief that phragmites were brought through soil and sediments that were placed in the lower levels of ships coming into the Atlantic coastal marshes. There are certain strains of phragmites native to the Great Lakes region, but these do not grow as rapidly or aggressively. The Great Lakes Informative Network explains, "the non-native strain of phragmites has spread pervasively through the Great Lakes region and other regions of the United States by both natural and human-driven dispersal mechanisms." (http://www.great-lakes.net/envt/flora-fauna/invasive/pdf/phragmites_glc_factsheet_2011.pdf) Non-native phragmites have been intentionally introduced to some areas as a tool to stabilize shorelines in restoration projects and as a filter plant in water treatment lagoons. (http://www.great-lakes.net/envt/flora-fauna/invasive/pdf/phragmites_glc_factsheet_2011.pdf) The Michigan Natural Features Inventory (and its partners) have also implemented a project which develops a regional network to detect and control non-native Phragmites located along more than 100 miles of Michigan’s Lake Huron shoreline. (http://www.fws.gov/GLRI/2010WatershedRestorationGrantsInvasive.htm) However, as seen in the picture above, the different strains of phragmites look almost identical. Trying to combat non-native species, while promoting the health of native ones, can be very difficult within the Great Lakes.

Asian Carp

Types of invasive Asian carp found in the Great Lakes.

The Great Lakes Restoration Initiative also works to protect the Great Lakes from species who may possibly threaten them in the future. The Asian carp, for example, have yet to be established in the Great Lakes ecosystem, many consider the threat of their invasion unavoidable. The Great Lakes Information Network claims, "Asian carp populations have thrived in the Mississippi River and connected waterways, causing extensive impacts. Asian carp have migrated toward Lake Michigan through the Illinois River and the Chicago Sanitary and Ship Canal (CSSC)." The rate of reproduction among these Asian carp is incredibly fast and they are capable of withstanding multiple types of climate. These fish are capable of easting vast amounts of food, including many of the fish, mollusks, and other invertebrates native to the Great Lakes. These fish could cause devastation to the incredibly valuable fisheries of the Great Lakes. The Environmental Protection Agency explains that, "To prevent Asian carp from entering the Great Lakes, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, U.S. EPA, the State of Illinois, the International Joint Commission, the Great Lakes Fishery Commission, and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service are working together to install and maintain a permanent electric barrier between the fish and Lake Michigan." Great Lakes environmental protection and natural resource agencies have formed an Asian Carp Regional Coordinating Committee to respond to information as it becomes available. Their coordinated approach is described in the Asian Carp Control Strategy Framework. GLRI funding is helping to implement actions described in that Framework such as developing innovative control technologies and detection/removal of Asian carp from the system.

There are multiple projects in the planning phase that will help combat invasive species. One example is the Sustain Our Great Lakes (SOGL) program, which is a public–private partnership among ArcelorMittal, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, the National Fish and Wildlife Foundation, the Natural Resources Conservation Service, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, and the U.S. Forest Service, that allocates one million dollars to projects that focus on combating invasive species in the Great Lakes. The over all goal of the GLRI, when it comes to invasive species, is institute a “zero tolerance policy” as a long term goal toward new invasions, including the development of ballast water technology, an early detection surveillance program, and a rapid response capability to address threats from new invasive species

3. Nearshore health and non-point source pollution: The nearshore and open waters are incredibly important. These waters provide habitat for numerous species of birds, fish and other aquatic life and also drinking water for communities. This area is where most residents and visitors experience the Great lakes through fishing, boating, and other recreational activities.

Map signifying areas with nearshore water in the Great Lakes.

Unfortunately, the nearshore areas of the Great Lakes have become seriously degraded due to eutrophication. Eutrophication, as explained by the Action Plan, is "The process by which a water body is enriched by nutrients such as phosphorus, resulting in excessive growth of algae, depletion of

dissolved oxygen, and other impacts, including beach closings." The factors of this problem include excessive nutrient loadings from both point

and non-point sources; bacteria and other pathogens

responsible for outbreaks of botulism and beach

closures; development and shoreline hardening that

disrupt habitat and alter nutrient and contaminant

runoff; and agricultural practices, which increase

nutrient and sediment loadings. Additional factors to the degradation of nearshore zones include invasive species, failing septic systems, inadequate pump-out stations for recreational boats, and grey water pipes (pipes containing non-hazardous household substances like soap).

Of all of these contributors, non-point sources are the main contributors of the pollutants causing the Great Lakes to degrade. Well, what exactly is a non-point source? To understand what a non-point source is, you must first understand what a point source is. According to the Environmental Protection Agency, "The term "point source" means any discernible, confined and discrete conveyance, including but not limited to any pipe, ditch, channel, tunnel, conduit, well, discrete fissure, container, rolling stock, concentrated animal feeding operation, or vessel or other floating craft, from which pollutants are or may be discharged. This term does not include agricultural storm water discharges and return flows from irrigated agriculture." Basically, a point source is one that can actually be identified and regulated. For example, the run off from industrial and sewage treatment plants. Non-point sources are not as easily identifiable. The Environmental Protection Agency explains that pollution from non-point sources are, "caused by rainfall or snowmelt moving over and through the ground. As the runoff moves, it picks up and carries away natural and human-made pollutants, finally depositing them into lakes, rivers, wetlands, coastal waters and ground waters." (http://water.epa.gov/polwaste/nps/whatis.cfm) The run-off of non-point sources are completely unregulated before entering water ways. Pollutants found in non-point run-off include excess fertilizers, herbicides and insecticides from agricultural lands and residential areas, the oil, grease and toxic chemicals from urban runoff and energy production, sediment from improperly managed construction sites, crop and forest lands, and eroding stream banks, salt from irrigation practices and acid drainage from abandoned mines, bacteria and nutrients from livestock, pet wastes and faulty septic systems and atmospheric deposition.

The non-point run off of main concern in the Great Lakes is that of agriculture. Thanks to the Farm Bill, agricultural areas are not considered a point source and therefore their run-off goes completely unregulated. Given the amount of pesticides, fertilizers, herbicides, and numerous other chemicals used in agriculture, the run off of agricultural zones needs to be regulated. Nutrients, like phosphorous and nitrogen, are what feeds the harmful algal blooms in the Great Lakes. Since regulating agricultural run-off would be an expense paid by farmers, they lobby heavily not in favor of this. The Farmers Union has a lot of power in the United States political system, and therefore keeps agricultural run-off regulation out of the question.

Of all of these contributors, non-point sources are the main contributors of the pollutants causing the Great Lakes to degrade. Well, what exactly is a non-point source? To understand what a non-point source is, you must first understand what a point source is. According to the Environmental Protection Agency, "The term "point source" means any discernible, confined and discrete conveyance, including but not limited to any pipe, ditch, channel, tunnel, conduit, well, discrete fissure, container, rolling stock, concentrated animal feeding operation, or vessel or other floating craft, from which pollutants are or may be discharged. This term does not include agricultural storm water discharges and return flows from irrigated agriculture." Basically, a point source is one that can actually be identified and regulated. For example, the run off from industrial and sewage treatment plants. Non-point sources are not as easily identifiable. The Environmental Protection Agency explains that pollution from non-point sources are, "caused by rainfall or snowmelt moving over and through the ground. As the runoff moves, it picks up and carries away natural and human-made pollutants, finally depositing them into lakes, rivers, wetlands, coastal waters and ground waters." (http://water.epa.gov/polwaste/nps/whatis.cfm) The run-off of non-point sources are completely unregulated before entering water ways. Pollutants found in non-point run-off include excess fertilizers, herbicides and insecticides from agricultural lands and residential areas, the oil, grease and toxic chemicals from urban runoff and energy production, sediment from improperly managed construction sites, crop and forest lands, and eroding stream banks, salt from irrigation practices and acid drainage from abandoned mines, bacteria and nutrients from livestock, pet wastes and faulty septic systems and atmospheric deposition.

The non-point run off of main concern in the Great Lakes is that of agriculture. Thanks to the Farm Bill, agricultural areas are not considered a point source and therefore their run-off goes completely unregulated. Given the amount of pesticides, fertilizers, herbicides, and numerous other chemicals used in agriculture, the run off of agricultural zones needs to be regulated. Nutrients, like phosphorous and nitrogen, are what feeds the harmful algal blooms in the Great Lakes. Since regulating agricultural run-off would be an expense paid by farmers, they lobby heavily not in favor of this. The Farmers Union has a lot of power in the United States political system, and therefore keeps agricultural run-off regulation out of the question.

Destructive Green Algae found in the Great Lakes.

The Great Lakes Restoration Initiative is considering many remedies to the algal bloom problem. They want to encourage the agricultural communities to use Best Management Practice (BMP's) possible. This is a voluntary action taken by the agricultural community, but government assistance and incentives are usually given. By using the Best Management Practice, farmers use alternative methods which minimize their environmental impact. The GLRI is also funding field-level research to determine what practices work best for specific kinds of soil type, crop

type, etc. Fertilizer applicator training is being funded by the GLRI, which teaches farmers the most efficient and environmentally safe was to apply fertilizers. Eventually, the people enforcing the Great Lakes Restoration Initiative, hope to take some sort of

legislation that bring meaningful changes in agricultural practices. The GLRI also wants to lower the discharge limits for phosphorus from wastewater treatment facilities. (Info from Jim's power point) Getting rid of combined sewer overflows would also benefit the Great Lakes water ways. Currently, storm water and sewage water are treated equally. This causes problems when a heavy rain fall occurs and treatment plants can not handle the large amount of water. When this occurs, the plants do not treat any of the water and let it flow directly into the lakes. Given that storm water is already clean, there is really no need to treat it. Without treating storm water, treatment plants could handle all of the sewage water and not let any flow untreated into the waterways.

4. Habitat and wildlife protection and restoration: To ensure health to the habitats and wildlife of the Great Lakes, ecosystems must be protected and restored. If the Great Lakes are healthy, they provide us with clean drinking water, rare wildlife populations, a variety of unique coastal habitats, wetlands which help control floodwaters, rivers which transport sediments, nutrients and organic materials throughout the watershed, forests which provide oxygen while reducing erosion and sedimentation, and upland habitats which produce topsoil and habitats for pollinators and bio-control agents. Also, fully functioning ecosystems shield the impacts of potential problems such as climate change.

There are a plethora of factors impacting the health of the Great Lakes habitats and wildlife. The Action Plan explains, "Habitat destruction and degradation due to development; competition from invasive species; the alteration of natural lake level fluctuations due to artificial lake level management and flow regimes from dams, drain tiles, ditches, and other control structures; toxic compounds from urban development, poor land management practices and non-point sources; and, habitat fragmentation have impacted habitat and wildlife." All of this has led to a decrease of biodiversity, poorly functioning ecosystems, and an altered food web.

4. Habitat and wildlife protection and restoration: To ensure health to the habitats and wildlife of the Great Lakes, ecosystems must be protected and restored. If the Great Lakes are healthy, they provide us with clean drinking water, rare wildlife populations, a variety of unique coastal habitats, wetlands which help control floodwaters, rivers which transport sediments, nutrients and organic materials throughout the watershed, forests which provide oxygen while reducing erosion and sedimentation, and upland habitats which produce topsoil and habitats for pollinators and bio-control agents. Also, fully functioning ecosystems shield the impacts of potential problems such as climate change.

There are a plethora of factors impacting the health of the Great Lakes habitats and wildlife. The Action Plan explains, "Habitat destruction and degradation due to development; competition from invasive species; the alteration of natural lake level fluctuations due to artificial lake level management and flow regimes from dams, drain tiles, ditches, and other control structures; toxic compounds from urban development, poor land management practices and non-point sources; and, habitat fragmentation have impacted habitat and wildlife." All of this has led to a decrease of biodiversity, poorly functioning ecosystems, and an altered food web.

The Great Lakes Restoration Initiative provides funding to many projects working to restore and preserve the habitat and wildlife of the Great Lakes. As implementation of the Great Lakes Fish and Wildlife Restoration Act, GLRI funding will be used to promote proposals and projects that will enhance populations of lake sturgeon, brook trout, migratory birds, threatened and endangered species, and other native aquatic and terrestrial species of fish and wildlife within the Great Lakes Basin. (http://www.fws.gov/GLRI/HabitatRestorationAct.htm) The Great Lakes shorelines have great potential in the wind power industry. Since this is also an area of major bird migrations, GLRI funding is being used to identify areas where wind development could be conducted safely and areas where it is likely to have the most negative impacts on birds. In order to combat the destruction caused by development, the GLRI works to ensure that development activities are planned and carried out in ways that are considerate of the environment and in harmony with fish, wildlife, and their habitats. The Great Lakes Restoration Initiative states in the Action Plan, that they will have 82% of recovery actions for federally listed priority species implemented by 2014. The GLRI also plans on having 4,500 miles of Great Lakes rivers and tributaries to be reopened and 450 barriers to fish passage to be removed or bypassed by 2014. Through these projects, and the numerous others not mentioned, the GLRI works to restore and protect the habitats and wildlife of the Great Lakes.

5. Accountability, Education, Monitoring, Evaluation, Communication and Partnerships: This focus area, can be considered the back bone for success in the others. In order for the Action Plan to succeed, having the most current information available that pertains to measuring and monitoring key indicators of overall ecosystem functions, evaluating restoration progress, and the information decision makers need, is crucial. This Initiative establishes the foundation for routine ecosystem assessments and must be as up to date as possible. This system needs to track progress of individual grant recipients and partner-led initiatives, as well as overall progress in meeting the short- and long- term goals and objectives of the Initiative as a whole. Aside from being most current, this information needs to be organized and presented to decision makers in a way that allows them to see the progress being made.

Education and outreach are also important aspects to the Initiative. By educating the up and coming decision makers of tomorrow, the GLRI can help them continue the efforts being put forth to restore the Great Lakes. Having information available to the public so they can see how important these waterways are is crucial. The GLRI funds numerous online information sites on the Great Lakes.

Many people have a say in what goes on in the Great Lakes; two countries, eight U.S. states, two Canadian provinces, 83 U.S. counties, thousands of cities and towns, 33 U.S. tribal governments and more than 60 recognized First Nations in Canada. Luckily, through out history there has been a shared concern by all of these groups for the protection and restoration of the Great Lakes. The partnerships in place between many of these governments must continue, and grow stronger, to address the complex issues faced by the Great Lakes.

From discussing the Great Lakes with Jim, and our professor Tait, it is clear to me how important they are. If utilized correctly, the Great Lakes could supply nine out of ten American's with fresh water. As water becomes more and more scarce, restoring and protecting the Great Lakes becomes even more important. Unfortunately, most of the projects the GLRI funds are still in the planning phase. Jim Lehnen explained that the Great Lakes Restoration Initiative has allowed for lots of research and observation, but now it is time for solutions and results. The Great Lakes Restoration Initiative is supposed to be updated at the end of this year. Hopefully, all the research and monitoring that has been done will allow for some forward movement on all of the projects the GLRI funds.

After our discussion with Jim Lehnen, we drove to Love Canal which is located in Niagara Falls, New York. Here we met with Mike Basile, a public affairs specialist for the Environmental Protection Agency of New York. Love Canal is of significance because it is a Superfund cite. Superfund is an environmental program established to address abandoned hazardous waste sites.

So, what happened at Love Canal? Well, William T. Love believed that by digging a short canal between the upper and lower Niagara Rivers, power could be generated cheaply to fuel the industry and homes of his would-be model city. (http://www.epa.gov/aboutepa/history/topics/lovecanal/01.html) Unfortunately, Nikola Tesla's discovery of how to transmit electricity over great distances by means of an alternating current ruined Love's plans. Love then sold the area to Hooker Chemical who converted it to a municipal and industrial waste dumpsite. In 1953, the canal was filled in with dirt and sold to the city for a whopping one dollar. (http://www.epa.gov/aboutepa/history/topics/lovecanal/01.html) At this time, the city was expanding outwards and had encompassed the canal. Hooker Chemical warned the cities school board not to build a school on the site, but they did it anyway. Sure enough, 25 years later it was discovered that 82 different compounds, 11 of them suspected carcinogens, had been percolating upward through the soil. The drum containers, originally containing these toxic chemicals, were rotting and leaching their contents into the backyards and basements of 100 homes surrounding the canal and the school built on top of it. One of the most prevalent chemicals found in Love Canal was benzene, a known human carcinogen, and one detected in high concentrations. Numerous cases of birth defects and sickness' were reported and assumed to be related to the toxics left in Love Canal. (http://www.epa.gov/aboutepa/history/topics/lovecanal/01.html)

The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) bought out 900 homes in the Love Canal area. Basile explained that the only reason so many homes were bought out, is because the EPA was such a new organization at the time and they were not really sure how to handle the situation. If the same situation were to occur today, probably less than half the amount of homes would be bought out. There were five home owners who refused to move, even after multiple offers by the EPA to buy their houses. Some of those people actually still live there, in the original house and everything. The EPA executed landfill containment, leachate collection and treatment and the removal and ultimate disposition of the contaminated sewer and creek sediments and other wastes, at Love Canal. (http://www.epa.gov/region2/superfund/npl/0201290c.pdf) The area is now deemed one of the safest places to live in the United States. Not sure how accurate that statement is, but Mike Basile seemed to feel strongly about it. When driving around the area of Love Canal, the newly restored neighborhood seemed perfectly normal and functioning. Still, I would not be caught living there. Basile explained that by experiencing the event of Love Canal, the people who were effected by it became more environmentally conscious and educated.

So, where does the money for Superfund activities come from? The United States Government Accountability Office explains that the funding from this program come from, "The Superfund trust fund has received revenue from four major sources: taxes on crude oil and certain chemicals, as well as an environmental tax assessed on corporations based upon their taxable income; appropriations from the general fund; fines, penalties, and recoveries from responsible parties; and interest accrued on the balance of the fund."

(http://www.gao.gov/new.items/d08841r.pdf) No matter where the money comes from, it is important that it is there. There are 120 Superfund cites within New Jersey and two thirds of them are actually considered worse than Love Canal. Being prepared for events like this is crucial, but perhaps we should work on funding preventative methods first and foremost.

After Love Canal, we drove to Buffalo, New York. Unfortunately, Buffalo was the most bland and boring city I have ever experienced. Given, we were only there for an hour or so and did not see every part of the city, but I doubt there was much more to see.

Cites used in this post:

(http://greatlakesrestoration.us/granteeinfo.html)

(http://www.epa.gov/osw/hazard/tsd/pcbs/pubs/about.htm)

(http://www.fws.gov/GLRI/2010LegacyActSediment.htm)

(http://www.fws.gov/GLRI/2010LegacyActSediment.htm)

(http://www.fws.gov/GLRI/documents/glri_actionplan[1].pdf)

(http://www.great-lakes.net/envt/flora-fauna/invasive/invasive.html)

(http://www.great-lakes.net/envt/flora-fauna/invasive/invasive.html)

(http://www.seagrant.umn.edu/ais/fieldguide#zebra)

(http://www.great-lakes.net/envt/flora-fauna/invasive/asiancarp.html)

(http://www.epa.gov/greatlakes/invasive/asiancarp/index.html)

(http://www.fws.gov/GLRI/documents/glri_actionplan[1].pdf)

(http://www.fws.gov/GLRI/documents/glri_actionplan%5B1%5D.pdf)

5. Accountability, Education, Monitoring, Evaluation, Communication and Partnerships: This focus area, can be considered the back bone for success in the others. In order for the Action Plan to succeed, having the most current information available that pertains to measuring and monitoring key indicators of overall ecosystem functions, evaluating restoration progress, and the information decision makers need, is crucial. This Initiative establishes the foundation for routine ecosystem assessments and must be as up to date as possible. This system needs to track progress of individual grant recipients and partner-led initiatives, as well as overall progress in meeting the short- and long- term goals and objectives of the Initiative as a whole. Aside from being most current, this information needs to be organized and presented to decision makers in a way that allows them to see the progress being made.

Education and outreach are also important aspects to the Initiative. By educating the up and coming decision makers of tomorrow, the GLRI can help them continue the efforts being put forth to restore the Great Lakes. Having information available to the public so they can see how important these waterways are is crucial. The GLRI funds numerous online information sites on the Great Lakes.

Many people have a say in what goes on in the Great Lakes; two countries, eight U.S. states, two Canadian provinces, 83 U.S. counties, thousands of cities and towns, 33 U.S. tribal governments and more than 60 recognized First Nations in Canada. Luckily, through out history there has been a shared concern by all of these groups for the protection and restoration of the Great Lakes. The partnerships in place between many of these governments must continue, and grow stronger, to address the complex issues faced by the Great Lakes.

From discussing the Great Lakes with Jim, and our professor Tait, it is clear to me how important they are. If utilized correctly, the Great Lakes could supply nine out of ten American's with fresh water. As water becomes more and more scarce, restoring and protecting the Great Lakes becomes even more important. Unfortunately, most of the projects the GLRI funds are still in the planning phase. Jim Lehnen explained that the Great Lakes Restoration Initiative has allowed for lots of research and observation, but now it is time for solutions and results. The Great Lakes Restoration Initiative is supposed to be updated at the end of this year. Hopefully, all the research and monitoring that has been done will allow for some forward movement on all of the projects the GLRI funds.

After our discussion with Jim Lehnen, we drove to Love Canal which is located in Niagara Falls, New York. Here we met with Mike Basile, a public affairs specialist for the Environmental Protection Agency of New York. Love Canal is of significance because it is a Superfund cite. Superfund is an environmental program established to address abandoned hazardous waste sites.

So, what happened at Love Canal? Well, William T. Love believed that by digging a short canal between the upper and lower Niagara Rivers, power could be generated cheaply to fuel the industry and homes of his would-be model city. (http://www.epa.gov/aboutepa/history/topics/lovecanal/01.html) Unfortunately, Nikola Tesla's discovery of how to transmit electricity over great distances by means of an alternating current ruined Love's plans. Love then sold the area to Hooker Chemical who converted it to a municipal and industrial waste dumpsite. In 1953, the canal was filled in with dirt and sold to the city for a whopping one dollar. (http://www.epa.gov/aboutepa/history/topics/lovecanal/01.html) At this time, the city was expanding outwards and had encompassed the canal. Hooker Chemical warned the cities school board not to build a school on the site, but they did it anyway. Sure enough, 25 years later it was discovered that 82 different compounds, 11 of them suspected carcinogens, had been percolating upward through the soil. The drum containers, originally containing these toxic chemicals, were rotting and leaching their contents into the backyards and basements of 100 homes surrounding the canal and the school built on top of it. One of the most prevalent chemicals found in Love Canal was benzene, a known human carcinogen, and one detected in high concentrations. Numerous cases of birth defects and sickness' were reported and assumed to be related to the toxics left in Love Canal. (http://www.epa.gov/aboutepa/history/topics/lovecanal/01.html)

The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) bought out 900 homes in the Love Canal area. Basile explained that the only reason so many homes were bought out, is because the EPA was such a new organization at the time and they were not really sure how to handle the situation. If the same situation were to occur today, probably less than half the amount of homes would be bought out. There were five home owners who refused to move, even after multiple offers by the EPA to buy their houses. Some of those people actually still live there, in the original house and everything. The EPA executed landfill containment, leachate collection and treatment and the removal and ultimate disposition of the contaminated sewer and creek sediments and other wastes, at Love Canal. (http://www.epa.gov/region2/superfund/npl/0201290c.pdf) The area is now deemed one of the safest places to live in the United States. Not sure how accurate that statement is, but Mike Basile seemed to feel strongly about it. When driving around the area of Love Canal, the newly restored neighborhood seemed perfectly normal and functioning. Still, I would not be caught living there. Basile explained that by experiencing the event of Love Canal, the people who were effected by it became more environmentally conscious and educated.

So, where does the money for Superfund activities come from? The United States Government Accountability Office explains that the funding from this program come from, "The Superfund trust fund has received revenue from four major sources: taxes on crude oil and certain chemicals, as well as an environmental tax assessed on corporations based upon their taxable income; appropriations from the general fund; fines, penalties, and recoveries from responsible parties; and interest accrued on the balance of the fund."

(http://www.gao.gov/new.items/d08841r.pdf) No matter where the money comes from, it is important that it is there. There are 120 Superfund cites within New Jersey and two thirds of them are actually considered worse than Love Canal. Being prepared for events like this is crucial, but perhaps we should work on funding preventative methods first and foremost.

After Love Canal, we drove to Buffalo, New York. Unfortunately, Buffalo was the most bland and boring city I have ever experienced. Given, we were only there for an hour or so and did not see every part of the city, but I doubt there was much more to see.

Cites used in this post:

(http://greatlakesrestoration.us/granteeinfo.html)

(http://www.epa.gov/osw/hazard/tsd/pcbs/pubs/about.htm)

(http://www.fws.gov/GLRI/2010LegacyActSediment.htm)

(http://www.fws.gov/GLRI/2010LegacyActSediment.htm)

(http://www.fws.gov/GLRI/documents/glri_actionplan[1].pdf)

(http://www.great-lakes.net/envt/flora-fauna/invasive/invasive.html)

(http://www.great-lakes.net/envt/flora-fauna/invasive/invasive.html)

(http://www.seagrant.umn.edu/ais/fieldguide#zebra)

(http://www.great-lakes.net/envt/flora-fauna/invasive/asiancarp.html)

(http://www.epa.gov/greatlakes/invasive/asiancarp/index.html)

(http://www.fws.gov/GLRI/documents/glri_actionplan[1].pdf)

(http://www.fws.gov/GLRI/documents/glri_actionplan%5B1%5D.pdf)

No comments:

Post a Comment